One day this spring, my students took it upon themselves to organize an especially elaborate play scenario. It began when a student brought me a cup of (imaginary) milk. I playfully asked, “What is this? A milk shop?” to which she replied, “Yes, it is!” Soon, most of the class was participating. This sort of thing happens all of the time, of course. But this particular episode was remarkable for its complexity and for the extent to which students organically incorporated lessons from throughout the school year.

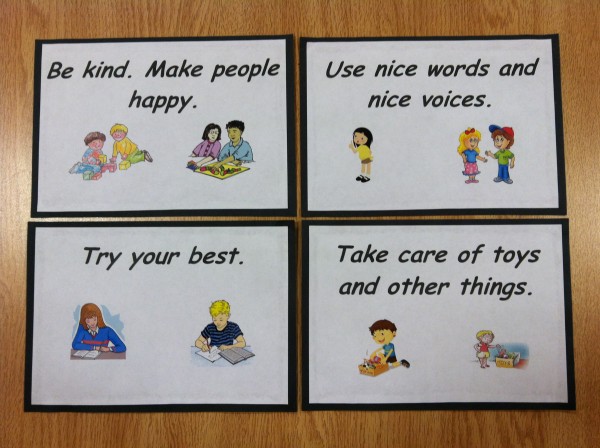

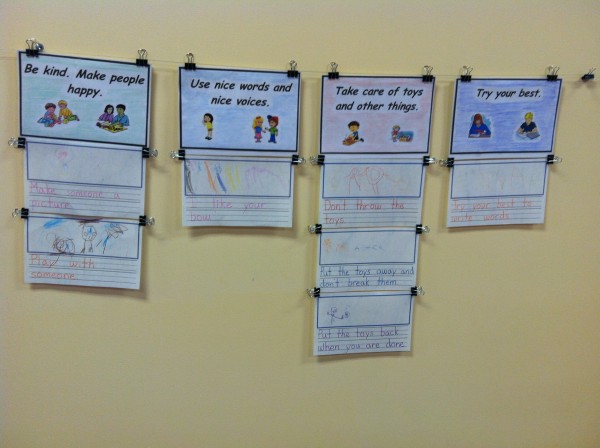

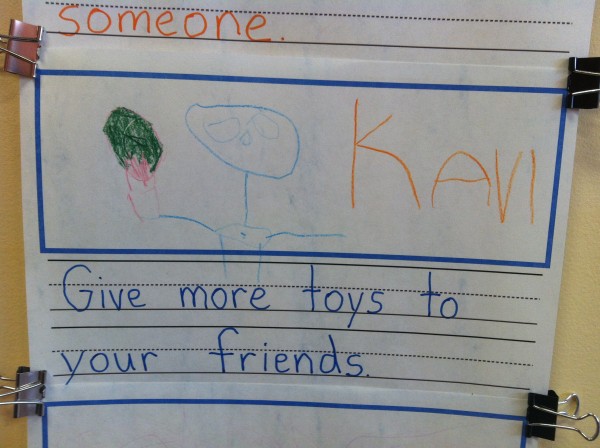

For one thing, everyone behaved with outstanding kindness. The usual leaders emerged, as expected, but they were welcoming of their peers’ ideas. I didn’t hear anyone reject anyone else’s suggestions. At one point, I heard a student ask, “Do you want to make a sign?” Often, children are inclined to make more commanding statements like, “You make the sign.” But our students are gradually learning to use more considerate language. In another instance, a student realized that one of her friends is allergic to dairy and therefore decided that she should sell almond milk, too.

But I was most surprised by the ways that students skillfully incorporated academics, often without any encouragement. For example, students naturally took to negotiating the price of milk (something that we practice regularly). They also began counting coins and plastic chips while making their purchases.

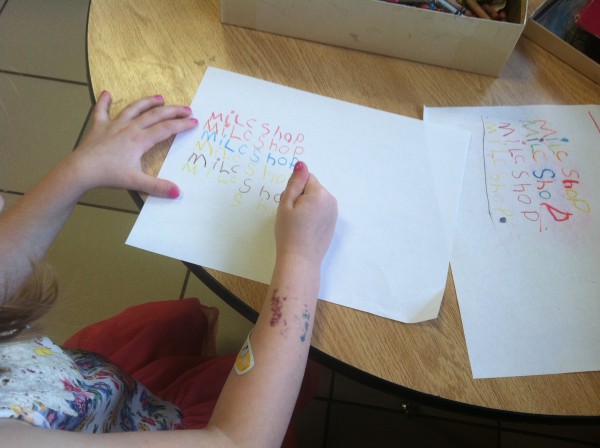

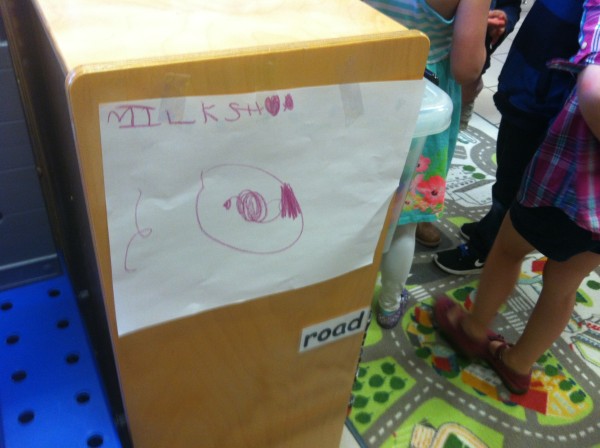

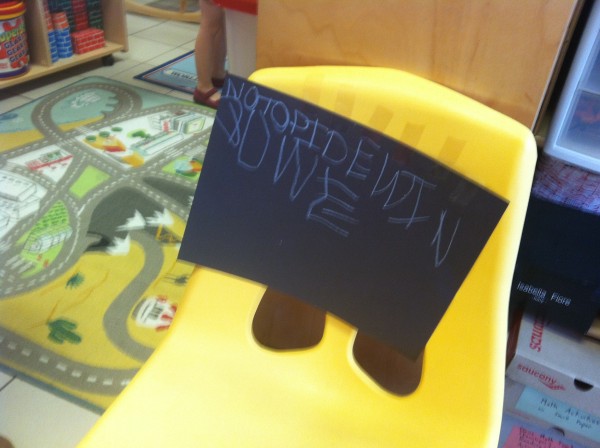

Then one student decided that the shop needed a sign. A few others agreed and they headed off to grab some art supplies. If this had happened back in the fall, each of these students would have asked me how to spell ‘milk’ and ‘shop.’ But this group has become so much more independent and confident since then that they made their signs without any support.

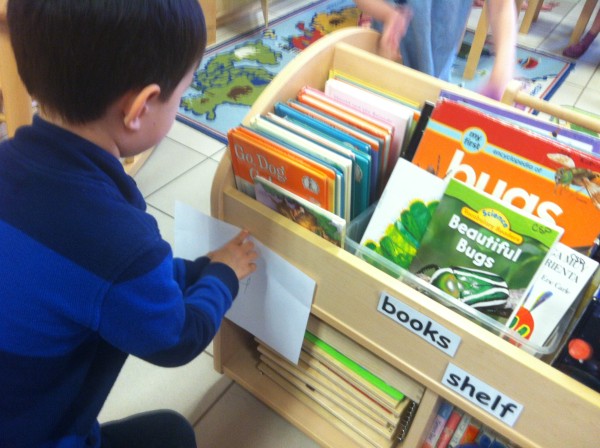

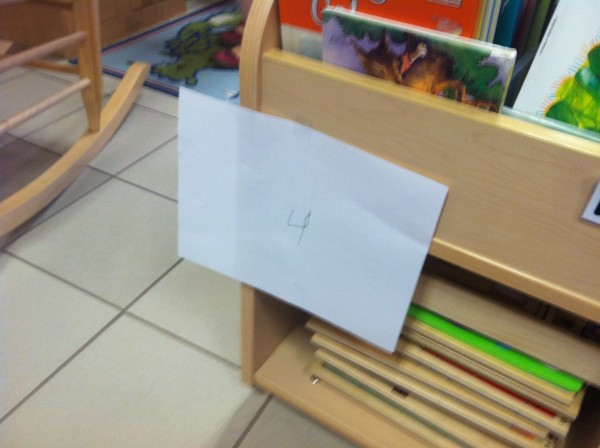

When the children decided to close the milk shop for a short while, another group of signs told customers that the doors would reopen at 4.

As promised, when the (toy) clock struck 4, the doors opened once again.

I have been feeling quite nostalgic recently, as I’ve recently announced that I am relocating to Washington, DC. I am going to miss my students, their families, and my coworkers quite a lot. This is but one example of the many memorable days I’ve had. I wish I had time to write them all down.