One day last spring, near the middle of April, one of my students noticed a web of some kind high up in one of the trees on our playground. Soon, a group of children had gathered and they began to discuss what had caused the mysterious web.

I had a pretty good idea what it was, but I kept my thoughts to myself. It’s not all that common for children to come across such a unique and fascinating phenomenon. I wanted them to practice thinking of possible explanations. It’s hard, sometimes, to hold your tongue when you have the knowledge your students are seeking. But if you want them to learn not just the facts but also the processes that produce those facts, you have to allow for some struggle. Most students concluded that some kind of spider had made the web. One student thought that it could be part of the tree.

A few days later, I noticed that there were a few more webs in the same tree. One web was within my reach. I decided to break off its branch, so that we could observe it in the classroom.

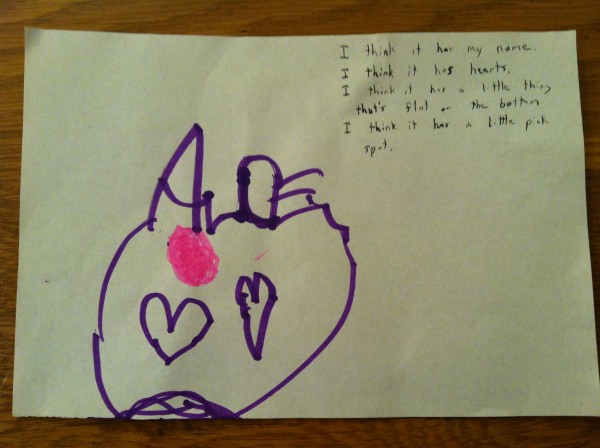

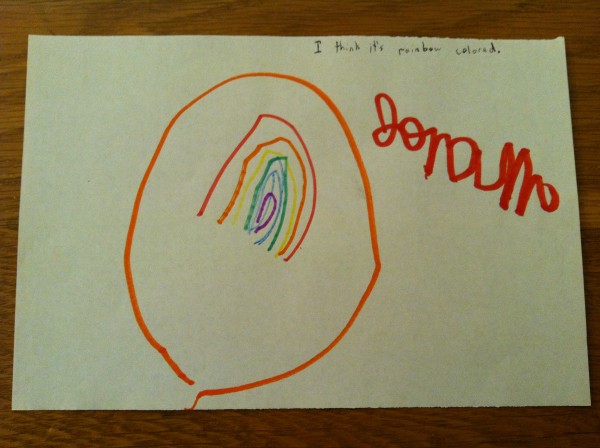

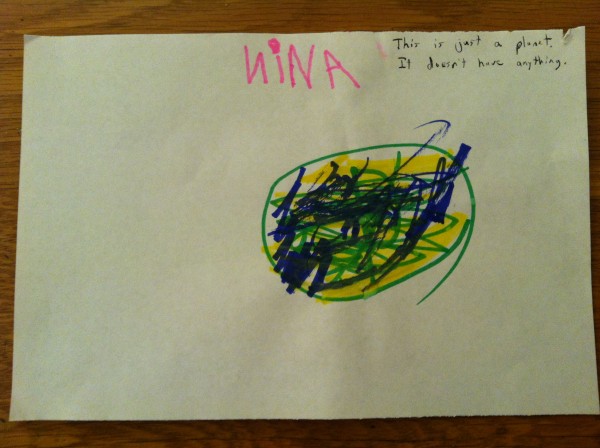

Right away, the children saw that inside of the web was a group of caterpillars. At this point, I said, “Oh! I think these are called tent caterpillars.” We did a little bit of research and determined that there are two varieties of tent caterpillar that live here in DC. I printed pictures of those two varieties, which the children compared to our caterpillars. Everyone agreed that we had captured eastern tent caterpillars (Malacosoma americanum).

We kept the caterpillars for about two weeks. They spent most of their time hiding in the middle of their web, but they occasionally ventured out in groups, crawled around, expanded their web, and munched on leaves. We expected, based on our research, that they would consistently emerge at specific times of day. However, we were never able to identify a reliable pattern. They often came out shortly before lunch, but not every day.

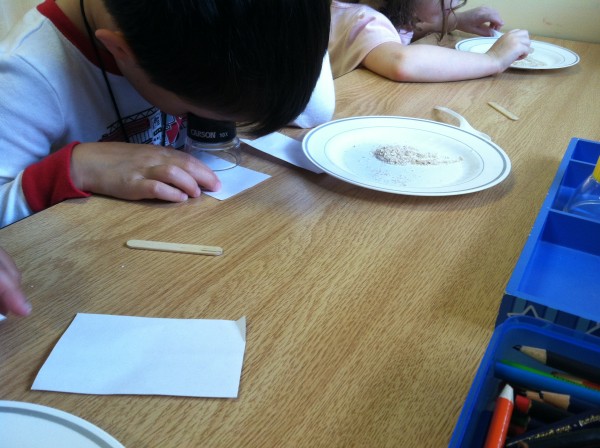

As we continued to research eastern tent caterpillars, we read somewhere that they can live in various types of trees. I suggested that we could do an experiment to see if our caterpillars would eat different leaves. We started by adding a leafy branch from one new tree. The caterpillars didn’t take a single bite from it. One student observed that those leaves smelled “spicy,” and suggested that, “maybe they don’t like spicy leaves.” So we put in two other varieties of leaves, neither of which smelled spicy (according to our budding scientists). The caterpillars ignored those, too. We were skeptical, and rightfully so. I later learned that we had been misinformed in our research; it seems that eastern tent caterpillars only live on one family of trees.

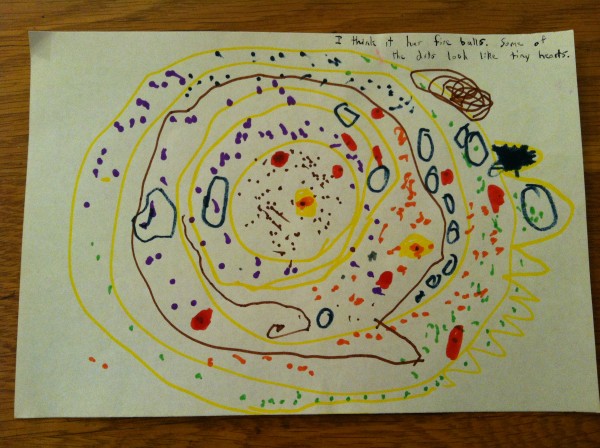

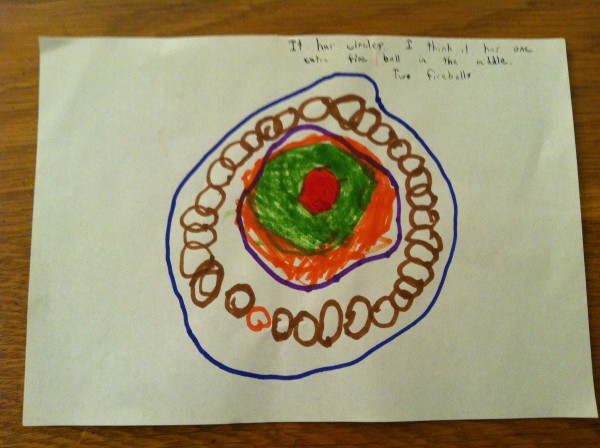

The children also observed that there were little black balls in the caterpillars’ web. I was sure it was waste, but most of the children thought they were eggs. We took some out and put them in a small container, in order to test the egg hypothesis. Nothing happened, of course. A week later, we observed one of the caterpillars pooping. “I think it’s laying an egg,” one student proposed. I explained that it’s moths and butterflies that lay the eggs, not caterpillars. That convinced everyone that we were dealing with poop, not eggs.

Out on the playground, I combed over the caterpillars’ home tree and found something that looked more like tent caterpillar eggs: a bump on a branch that was likely caused by an insect of some kind. I broke it off and brought it back to the classroom. Alas, nothing ever came out of it; whatever was in there had probably already hatched, perhaps years ago.

The caterpillars’ waste had built up rapidly, and it had begun to stink, so we decided it was time to let them go. We released them one by one, carefully placing them back onto the tree where we had found them.

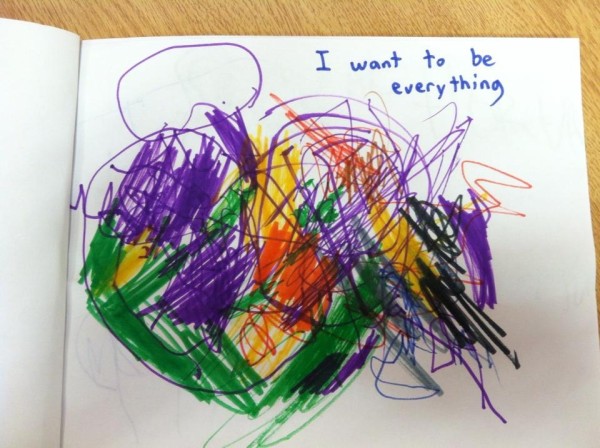

We saved four caterpillars, in the hopes that they would form cocoons, and two of them did. A couple of weeks later, we had two healthy-looking lappet moths. They weren’t very exciting as pets. They changed positions at night, but nobody ever saw them move. We tried putting the cage in a dark closet, hoping that it would awaken their nocturnal instincts. Still, they stayed put. When we took them outside to release them, I was able to get them to crawl onto a slice of orange. The first rested there for about a minute and then took flight. It flew directly to the bark of a small tree. A group of children followed it and one of them exclaimed, “It’s camouflaged!”

I don’t know if this particular set of activities is replicable. But, I wanted to share it because it demonstrates the potential richness of learning experiences that incorporate nature. Plants and animals can stimulate children’s wonder and curiosity like nothing else. Whatever outdoor space you educators and parents have access to, I encourage you to make the most of it.